REED ALL ABOUT IT

SCI-FI AUTHOR IS WORLD-FAMOUS YET LITTLE-KNOWN IN HOME STATE

by Jeff Korbelik

Lincoln Journal Star -- Sunday, January 11, 2004, page 1K

In the basement of a tiny house

on a quiet street near Antelope Park, the most famous Nebraska

author you've never heard of follows his passion.

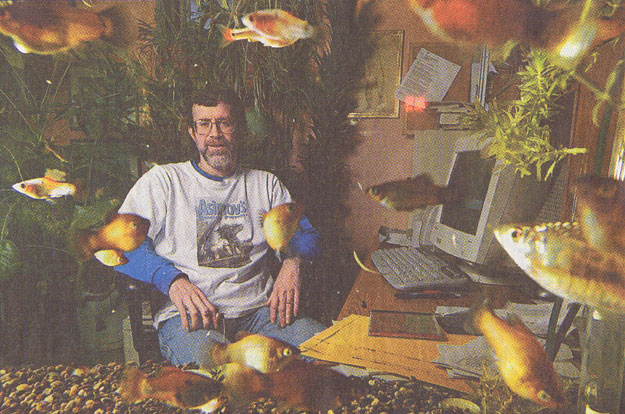

Sitting at a computer, surrounded

by an ecosystem of giant plants and an aquarium filled with fish

of various sizes and colors, science fiction author Robert Reed

lets his imagination fly.

He asks "what if."

What if the crew of a spaceship

discovers a planet within the ship's hull -- the premise of his

critically acclaimed novel Marrow.

Or what would happen if 1,000 people,

by their superior wisdom and abilities, are chosen to safeguard

humanity's future, as is the case in his latest book, Sister

Alice.

His creativity surprises even his

wife, Leslie.

"It's amazing to me a lot

of the time," she said. "Day-to-day life, he is very

prosaic, but when I read his stories, I say, 'My God, where did

this come from?'"

o o o

Robert "Bob" Reed,

47, relaxes on the couch in his living room. The early afternoon

sunlight pours through the picture window and bathes the Christmas

tree across from him.

The family dog, Roxy, a 10-year-old

brown and white Siberian Husky, snoozes in the corner. His 2-year-old

daughter Jessie's toys are scattered here and there on the floor.

The rail-thin Reed is in blue jeans.

He has pulled a black Lincoln Marathon T-shirt over a long-sleeve

white one.

The marathon shirt hints at his

passion for long-distance running. He can be found regularly

on Lincoln's streets and trails and competing in local road races.

His hair is dark and wavy, it and

his signature beard streaked with gray.

"Was there a turning point

in your career?" the interviewer asks.

Reed shakes his head and smiles

slyly in response to the question.

"It seems like there are turning

points, but there aren't," he says. "I mean, when I

made my first sale, I thought, 'Well, that's it, now I'm a writer.'

"The second sale I won the

Writers of the Future award, but I can't say it was anything

more than a nice little moment.

"The first novel...the first

time I was nominated for a Hugo...All these things I look back

on as moments, but not as turning points," he said.

Reed has published more than 100

works, including 10 novels, since winning the L. Ron Hubbard

Writers of the Future contest in 1986 -- one year before

he dedicated himself to writing full time.

Today he is considered one of the

top (and most prolific) science fiction authors in the world.

He is adored in France and loved in England.

His short stories appear regularly

in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and Asimov's

Science Fiction.

Sister Alice, released by

Tor in October, is available in the science fiction/fantasy sections

of most bookstores.

And though he has had no turning

points, he has had a few epiphanies, including a memorable one

in 1984 -- he remembers the year because, like most Nebraskans,

he can tie it to a significant football event such as losing

a national championship on a failed two-point conversion.

He had just moved to Dallas, where

he believed the bright, clear days would help open his mind and

aid him in becoming an accomplished writer.

Writers think that way.

"While I was there,"

he says, "I realized most of the writers I respected and

wanted to emulate all had terribly gray hair."

"In other words, this is a

slow business to have success in. There are exceptions, but for

the most part it's kind of like the last writer standing,"

he said.

When told he's beginning to show

signs of aging, he readily agrees and ends this part of the conversation

with a metaphor.

"I've got gray," he says.

"I've got plenty of gray. I'm creating a career slowly,

like a coral reef."

o o o

Reed was 12, maybe 13, when

he filled a couple of spiral notebooks with words.

"I tried to write a novel,"

he said. "It had one thing happening after another. It seemed

to be science fiction. It was a strange place with monsters.

I was heavy into monsters."

Uncharacteristically, Reed set

his pen aside and didn't pick it up again until college. He admits

he "obsessively" does things, from long-distance running

to writing to landscaping his back yard.

But for some reason, writing didn't

take hold back then.

"If I would have stayed with

writing, it definitely would have changed my life," he said.

The reason he came back to it:

He thought it would be an easy way to make money.

"I know, it was stupid,"

he said. "I was extremely naïve."

Money was also why he majored in

biology at Nebraska Wesleyan University.

"I always kind of thought

if I needed a job, that would be a really rich area to go into,"

he said.

But then he discovered he didn't

want to be a scientist. He learned he wasn't into lab work --

he worked as a technician at NWU from 1979 to 1980 -- or conducting

experiments.

Theory was a different story.

He found he was partial to such

subjects as quantum mechanics. This explains his penchant for

science fiction instead of mysteries, westerns or romance.

"I like science fiction because

it has ideas that interest me," he said.

o o o

Reed is a far cry from the stereotypical

science fiction author.

He didn't read a lot from the genre

growing up.

He still doesn't.

"I've never considered myself

a fan," he said. "I'm not in 'fandom.' I never attended

a convention until I was a writer."

Even his work is atypical.

Most of the industry comprises

novels, series and interrelated worlds and universes.

Reed prefers to jump from one idea

to the next, usually in short story form.

"I like to have an arena where

I can get the thing done," he said. "Play with the

concept, but not marry it. I don't want to live with it for months

on end."

There have been exceptions. He

just finished writing the sequel to Marrow, his biggest

commercial success. It's slated for release early next year.

"I enjoy this ship I built

and its possibilities, so I'm willing to spend more time with

it," he said.

And unlike some of his peers, he

avoids the limelight.

He probably is one of the most

celebrated Nebraska authors you've never heard about. His latest

novel is not on display at local bookstores. In fact, most of

his novels are available only at libraries or through mail order.

Granted, science fiction doesn't

stay in print long, which makes it difficult to showcase a writer.

But a more likely reason for Reed's

anonymity outsid sci-fi circles is his own selflessness. He is

not one to toot his own horn.

"He's not huge into publicity,"

said Scott Clark, a Reed fan and Web site manager for the local

science fiction club Star Base Andromeda.

"He appreciates the writing more than the self-promotion."

His friends acknowledge as much.

Running partner Marty Berger said their conversations rarely

are about Reed's profession.

"We talk all the time, but

we talk about sports (Reed is a Chicago Cubs baseball fan), about

gardening and about fish ponds," Berger said. "We talk

a lot about fish ponds. He's got me into them."

Reed said his wife, Leslie, a reporter

for the Omaha World Herald, has encouraged him to be more aggressive

about getting his name out there.

"She told me if I was a more

difficult writer, I would get better attention," he said.

"So I would start acting more difficult around the house,

and that talk would go away."

He smiles.

"In order to be a difficult

writer, you have to be a difficult person," he said.

And that's just not him.

When a conversation does turn to

writing, Reed discusses it in his own roundabout way.

He asks the listener to discern

his or her own meaning from his words.

Like his talk on self-expectation.

"When I was a kid," he

says, "my father would take (my brother and me) hunting,

and I remember how impatient he was with us."

"With me, I remember very

distinctively: I'm carrying a double-barreled 20-gauge shotgun

across the snow, and it's getting deep.

"I'm wading through this stuff, and (my father's) going,

'C'mon, c'mon, c'mon.'

"Now I have a 2-year-old,

and I find myself not yet doing that, but there seems to be a

pushing of expectations.

"It's a little frightening."

o o o

Not everybody appreciates Reed's

talent. He smiles again when told a local bookseller described

his work as "grim."

He has heard it before.

"It occurs to me, when I watch

other people's faces, that what I do for a living is a pretty

grim business.

"If I needed to put together

a resume, I would say I was one of the great experts at apocalyptic

crap. I can generate 100 ways in which the Earth dies."

His wife doesn't find his writing

depressing, though she may be biased. She finds it real.

"What I like is he does a

nice job of making (science fiction) human," she said. "You

recognize his characters as people."

Local fan Clark, too, noted the

emphasis on humanity rather than technology.

"There is a lot of deep emotion

in his stuff," Clark said. "Some of it is depressing,

but I find it engaging."

o o o

Like most writers, Reed draws

from the world around him.

From television. From Lincoln.

From his family. From the news.

He's inquisitive. He visits the

public library at least once a week.

Friend Kerry Eagan said their Saturday

morning conversations at a downtown coffee shop will range from

mad cow disease to inflation to what would happen if a comet

hit the Earth.

"He tells me of a number of

ways the Earth can be annihilated," Eagan said. "He

also tells me not to get too worried about this stuff."

Reed worked part time for nine

years (1978-87) in a Lincoln factory before becoming a full-time

writer. Factory work, he said, didn't influence his writing,

but it has affected him in other ways.

"Occasionally, I'll dream

I'm in the factory," he said. "That will help me write.

Not creatively, but more like a prod. I don't want to go back

there."

He's anxious to see if fatherhood

takes him in any new, wondrous directions. He knows he already

approaches writing dialogue differently.

"I had a debate with my daughter

this morning (about) whether she pooped or tooted," he said.

"It's a line of talk I never really imagined before."

Reed also is experimenting with

other genres. He's made a couple of tries at thrillers and has

penned a "running novel," though he's not sure how

to sell it.

"It doesn't have a distinct

and easily identifiable market," he said. "There isn't

a long line of running novels."

His agent told him there was money

in serial killers.

"I did the research and got

really depressed," he said. "That was the worst depression

I've had. I couldn't write anything about it."

He does know one thing: "My ability has gone up," he

said. "I've learned more about how to do this. I make mistakes,

but when I make mistakes, I know I've done it."

That's what makes it a whole lot

easier to respond to the "what ifs."

Reach Jeff Korbelik at 402-473-7213 or jkorbelik@journalstar.com

|